What is Alveolar Echinococcosis?

Alveolar echinococcosis is a rare but dangerous disease caused by the larvae of the small fox tapeworm (scientific name: Echinococcus multilocularis ). The larvae almost always settle in the liver first and can destroy the entire organ over the course of years through tumor-like growth if the infection is not diagnosed and treatment is not initiated in time. In advanced stages, the larval tissue can also grow into the abdominal cavity and infect the organs adjacent to the liver. In addition, individual particles of the larval tissue can detach and enter other organs via the blood or lymph flow, where they settle, e.g. in the lungs, brain, muscles, bones, etc.

At the beginning of the infection, there are hardly any symptoms that would raise suspicion of this disease. Even after many years, the first signs are non-specific (fatigue, abdominal pain, jaundice, etc.). At this point, the larval tissue in the body has usually already reached a considerable size.

Treatment

If the lesions in the liver are discovered early and are still small enough, the larval tissue is surgically removed from the healthy liver tissue as completely as possible. Patients must take specific medications for two years after the operation.

However, there are cases where surgery is not an option or the parasite tissue cannot be completely removed. These patients have to take medication for many years, usually for life. The antiparasitic preparations currently available inhibit the growth of the larval tissue, but cannot kill it completely. Only a strict dosage regimen and appropriate discipline on the part of the patient can prevent the spread of the parasite tissue and a new infestation of other organs.

There are currently only a few known cases in which the parasite was successfully fought and killed by the body's own immune system. The course of the disease is usually chronic: long-term medication prevents further growth of the larva and progressive damage to other organs, but the status of the disease must be regularly checked by a doctor. A vaccination against this dangerous infection is not yet possible.

How does a person become infected?

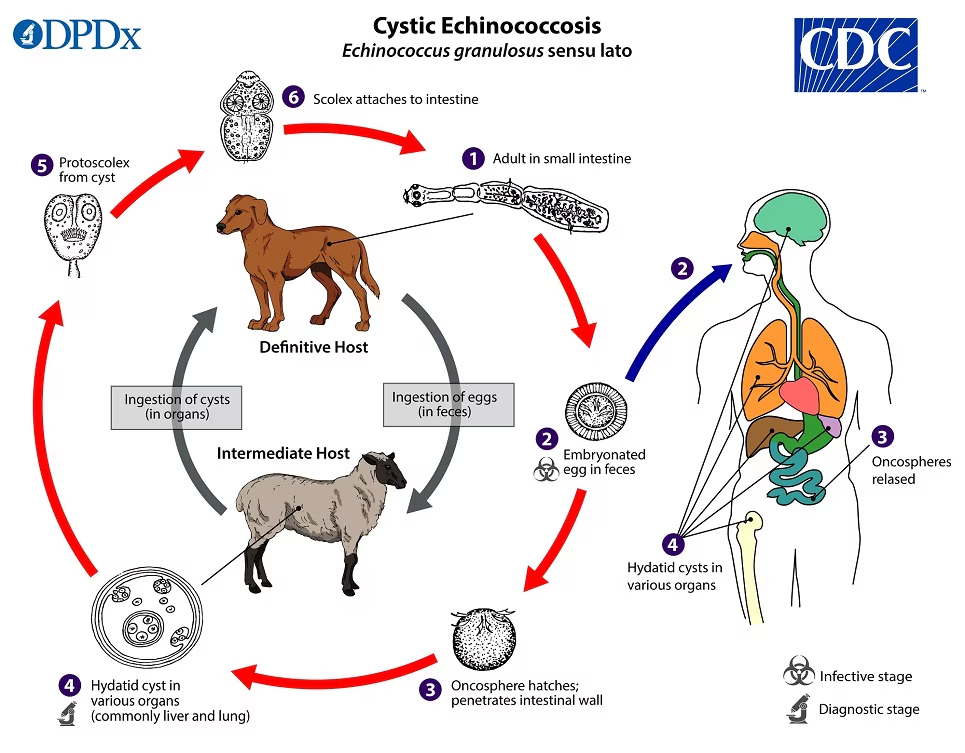

The fox tapeworm requires various animal species as host organisms for its development from egg to sexually mature worm. The adult worms live in the small intestine of carnivorous animals such as foxes, dogs or cats (but not martens and badgers). Here they produce thousands of eggs, which the host excretes in the faeces. Various rodents such as water voles, field mice, muskrats, etc. become infected with these eggs. In the intestine of the new host animals, the larvae hatch from the eggs and migrate to their liver, where they attach themselves, grow and reproduce. When a fox eats an infected rodent, the larvae anchor themselves in its intestinal mucosa and mature into adult tapeworms, which in turn release new eggs. This completes the natural cycle in wild animals (see life cycle diagram ).

Humans become infected when they ingest the tapeworm eggs through their mouth. The exact route of transmission is not known and cannot be directly investigated. The eggs are very resistant to various environmental influences outdoors and can survive for many months in cool and damp weather (for example, they can withstand temperatures below -18°C), but they die when heated to 60°C. There is therefore no risk of infection when eating sufficiently heated food; there is also no possibility of transmission from person to person.

In some areas of Europe, the cycle is constantly maintained in wild animals (foxes and rodents) ( endemic areas ). There is a risk of transmission here if possible host animals (foxes, dogs, cats) that excrete the tapeworm eggs and can carry them in their fur, for example, are touched directly, or if field or garden crops that could be contaminated with the animals' excrement are eaten raw (plants from fields or meadows or a garden that is not fenced in to prevent foxes). The eggs could also be transmitted during field work (contact with damp soil).

None of the transmission routes mentioned has been scientifically proven. Until there is more concrete evidence, some behavioral measures should be strictly observed in endemic areas:

wash your hands thoroughly after working in the field or in nature

Wash your hands thoroughly after contact with pets that catch and eat mice

Vegetables, salads and fruits from the field or from the unfenced garden should best only be consumed cooked or fried, or at least washed very thoroughly

Regularly administer the correct worming treatment to pets that catch and eat mice. Such treatment must be repeated every four weeks to ensure it is effective.

Distribution of the fox tapeworm in Europe

Infection rates in foxes: The small fox tapeworm occurs in the temperate to cold climate zones of the northern hemisphere. It is particularly widespread in Alaska and the tundra regions of Russia. In Europe, the parasite seemed to be restricted to a few endemic areas in southern Germany, eastern France, northern Switzerland and northwestern Austria. Since the 1990s, however, several studies have discovered it outside of these classic distribution areas, for example in Belgium, the Netherlands, northern Germany, Poland, the Czech Republic and the Slovak Republic (see distribution map ). It is still unclear whether the parasite has spread or whether the cycle existed earlier in the wild animals of these areas and was not discovered due to a lack of studies.

Infection rates of foxes with tapeworm vary considerably between regions. In large areas of eastern France (see distribution map ), southwestern Germany and northern Switzerland, infestation rates of over 50% have been recorded, while in other areas fox infestation rates may be less than 5%. In some areas, both the number of foxes and infection rates with fox tapeworm have increased dramatically over the past decade (see distribution map ). Recent studies have shown that foxes now live in large numbers in suburban and inner-city areas and can be infected with the tapeworm (see distribution map ). Domestic animals such as dogs and cats can also occasionally be infected, but there is not yet sufficient research on this.

Cases of illness in humans: The majority of patients reported to the register to date come from the known endemic areas in Europe. The number of patients is still small: since its establishment, 580 cases have been reported to the register from France (see distribution map ), Germany, Austria, Switzerland, Turkey, Poland and Greece (as of May 1999). In relation to the total population in these areas, echinococcosis appears to be only a regional problem. However, it is feared that more cases can be expected in the future, as a period of up to 10 years can elapse between infection and diagnosis. If the increase in fox infestation mentioned above has an effect on the risk of infection in humans, this will probably only become apparent in a few years. At present, no concrete statements can be made about how high the risk of infection really is in the endemic areas.

Why is a Europe-wide initiative addressing a rare disease?

As mentioned, alveolar echinococcosis is a rare disease that affects only a small number of people in certain regions. However, for the individual patient, it represents a considerable psychological burden: they have to live with a disease that can be life-threatening if not treated properly. The prospects of a definitive cure are currently slim and patients must accept lifelong medication and regular follow-up examinations. Treatment of echinococcosis is also very expensive: the annual cost of medication per patient is between EUR 5 000 and 15 000, and the cost of treatment over a patient's entire lifetime can add up to EUR 250 000. Furthermore, ignorance of the risks of transmission and concern for the health of children are causing anxiety in the population in endemic areas to a level comparable to the fear of rabies in the 1970s.

Unfortunately, the complex conditions that can facilitate transmission of the parasite to humans are not yet sufficiently understood. The key questions are how environmental factors influence the infestation rates in foxes and how transmission to humans can be prevented. The aim of the European Echinococcosis Register is therefore to determine the current distribution of the parasite in Europe and, in the long term, to obtain as accurate and complete information as possible on the infestation rates in animals and the incidence of the disease in humans. These data, collected from all affected countries, should make it possible to plan precise studies, for example on possible risk factors for transmission (human behaviour, the actual role of dogs and cats, occupational risks). If these studies succeed in establishing regional risk profiles, sensible and locally implementable strategies for preventing and controlling this serious disease can be developed.